There’s a long gap between my first Appendix N book, The Hobbit (paid link) — which was also my first Reading Appendix N book post, as I’m going in the order I read them — and my next one. One of my best friends in high school, Stephan, introduced me to H.P. Lovecraft by way of Call of Cthulhu (paid link), which he ran for my high school gaming group. I asked Stephan if reading some Lovecraft would diminish my enjoyment of the game, and he said it might, just a little, but it would be worth it; he was right about it being worth it.

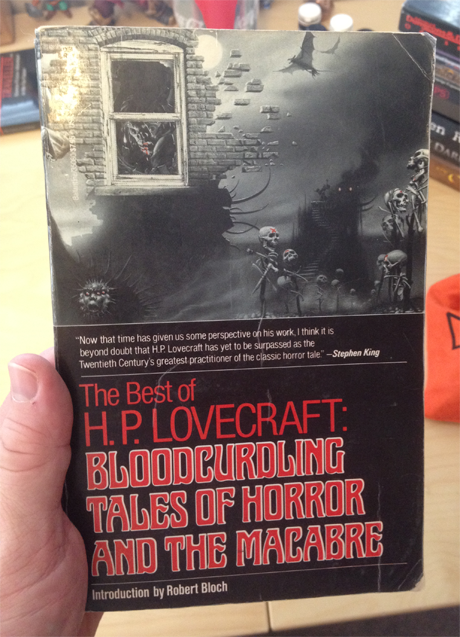

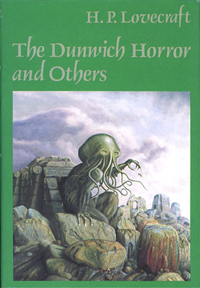

I snagged this collected edition, which is neither special or definitive, and read it so often that it now looks like this:

That book led me down the rabbit hole, and Lovecraft became one of my favorite authors. Over the next several years, I tracked down and read all of his fiction — and continued playing Call of Cthulhu, which remains one of my all-time favorite RPGs. My Lovecraft library, which includes several other authors in his circle, spans a shelf and a half in our library. It’s a special pleasure to have a chance to write about Lovecraft’s work in the context of Reading Appendix N.

Why This Book?

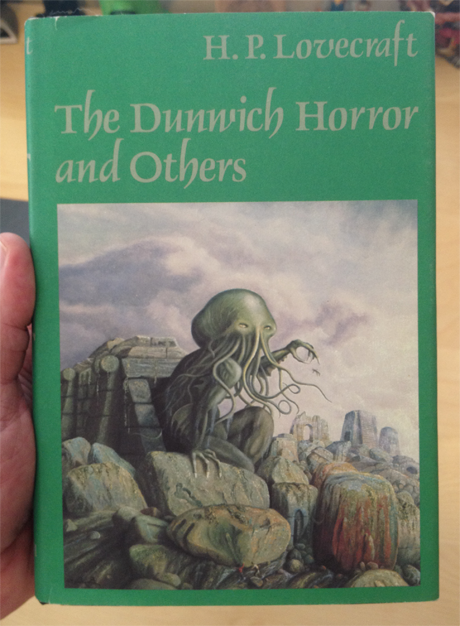

Lovecraft is among those authors in Appendix N for whom Gary didn’t recommend a specific title or series. Following my own guidelines for this project, I recommended a specific Lovecraft work based on personal experience: The Dunwich Horror and Others (paid link). Of all of the personal recommendations I made on the 100-book Appendix N reading list, this was the most difficult one to make.

I initially chose At the Mountains of Madness (paid link), which features one specific tale that feels very Appendix N-y to me: The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, a Dreamlands story of strange and peculiar lands and peoples. After some deliberation, though, I settled on The Dunwich Horror and Others because it includes four of my personal favorite Lovecraft stories — Pickman’s Model, The Colour Out of Space, The Whisperer in Darkness, and The Shadow Out of Time — as well as the seminal The Call of Cthulhu, and because it offers a sampling of different elements of Lovecraft’s approach to weird horror.

If you’re new to Lovecraft, this book is a great place to start. It’s packed with excellent stories, including many that I can still picture in my mind many years after my last reading (which is true of all the ones I listed above). They’re vivid, creepy, and fantastic.

With a gun to my head, I’d pick The Whisperer in Darkness as my overall favorite Lovecraft story, though it’s in close competition with At the Mountains of Madness and The Colour Out of Space. Here are two quotes from its first couple of pages which, without spoiling the story, are emblematic of Lovecraft in their own ways. First, the opening line:

Bear in mind closely that I did not see any actual visual horror at the end. To say that a mental shock was the cause of what I inferred–that last straw which sent me racing out of the lonely Akeley farmhouse and through the wild domed hills of Vermont in a commandeered motor at night–is to ignore the plainest facts of my final experience.

…and then the initial third-hand glimpses of strangeness in the hills, reported in the aftermath of a great flood:

What people thought they saw were organic shapes not quite like any they had ever seen before. Naturally, there were many human bodies washed along by the streams in that tragic period; but those who described these strange shapes felt quite sure that they were not human, despite some superficial resemblances in size and general outline. Nor, said the witnesses, could they have been any kind of animal known to Vermont. They were pinkish things about five feet long; with crustaceous bodies bearing vast pairs of dorsal fins or membranous wings and several sets of articulated limbs, and with a sort of convoluted ellipsoid, covered with multitudes of very short antennae, where a head would normally be.

One thing I love about Lovecraft’s stories set in New England — “Lovecraft Country” — is how grounded in, and evocative of, that part of the country they are. Having grown up in New York, and spent many happy days traipsing and driving around in New England, that region is now inextricably linked to Lovecraft for me. I also love his use of language, which is sometimes criticized for being overblown and overly long on description; his style works beautifully for the kinds of stories he writes.

I also love Lovecraft’s nihilistic universe — the elder gods and things between the stars aren’t evil, or out to get us; they know and care as little about us as we do about ants. It’s only when people begin worshiping them, learning from them, and misunderstanding them that evil enters into the picture. Even 70-plus years after many of these stories were written, that vision of the universe still feels fresh to me.

Above all, though, Lovecraft is a master of the weird, and of introducing the weird into the ordinary world of the 1920s and ’30s in horrifying ways. His protagonists tend to be bookish types, and given to curiosity past the point of caution; the more they learn, the worse things get. Sometimes they can’t help it, as in The Shadow Out of Time, wherein Nathaniel Peaslee’s mind is whisked out of his body and transplanted into a rubbery, tentacled, conical alien form light years away, and quite often they don’t entirely know what to make of the events that transpired, or how to continue on in a world whose veils have been drawn back for them.

In other words, he’s a damned fine horror writer, and his brand of horror is evocative and strange and wonderful and compelling — and it sticks with you. For my money, The Dunwich Horror and Others showcases all of those qualities superbly.

The Dunwich Horror and Others and AD&D

I’m fascinated about why Lovecraft made it into Appendix N, and I can only guess as the answer — assuming, of course, that the answer is other than the most basic option: Gary Gygax was influenced by Lovecraft in a non-specific way, and that influence informed the creation of AD&D. My best guess at a more direct connection, if indeed there is one, is the notion of protagonists ill-equipped to face the challenges ahead, trapped in a universe where the gods don’t care about them, who nonetheless explore cyclopean tombs and alien locales — often going mad, dying, or otherwise being irrevocably changed by their experiences — which matches up pretty well with old-school D&D.

Consider the average low-level adventuring party, little more than peasants with swords and the occasional spell, yet willing to delve into dark and dangerous dungeons, face unknown threats — often threats which far outclass them — and being changed by their experiences; squint a bit, and that’s a Lovecraft story. I could be way off-base, but when I look at Lovecraft’s tales and AD&D side by side, that’s the strongest connection I see. Others, like the presence of monsters and magic, seem a bit too general to explain why Lovecraft is part of Appendix N.

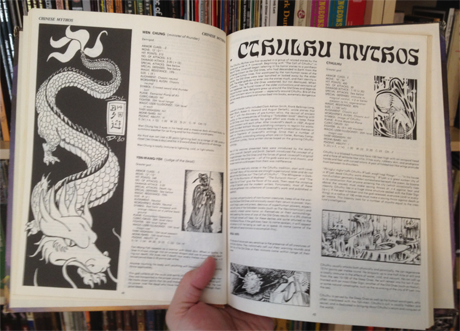

Later on, of course, came a much more obvious connection: Lovecraft’s gods made their way into the AD&D supplement Deities & Demigods (paid link). For legal reasons, the Cthulhu Mythos section was removed from later printings, turning the early ones into one of the best-known D&D collectibles.

Which edition?

Lovecraft was bound for likely obscurity when his work, largely unrecognized, was returned to print and eventually to the American consciousness by August Derleth. Derlath founded Arkham House, produced many editions of Lovecraft’s work, and championed him as one of the founding fathers of horror.

Unfortunately, he also altered the cosmology of Lovecraft’s universe to assign asinine elemental aspects (which didn’t exist in the originals) to beings like Cthulhu, and then introduced his own works to “fill in” the “gaps.” For better or worse, the term he coined to describe the mythology created in Lovecraft’s stories, “Cthulhu Mythos,” has stuck. (Lovecraft himself called his works in this vein “Yog-Sothothery.”)

Between those efforts and the vagaries of reprinting any author’s work many times over many years, and through many publishers, many older editions of Lovecraft’s tales aren’t accurate. Luckily, Arkham House retained S.T. Joshi to edit Lovecraft’s work, and Joshi’s fidelity to his source material is, frankly, fucking amazing. He’s a scholar, detail-oriented and dedicated to preserving Lovecraft as Lovecraft, and his editions are both excellent and definitive.

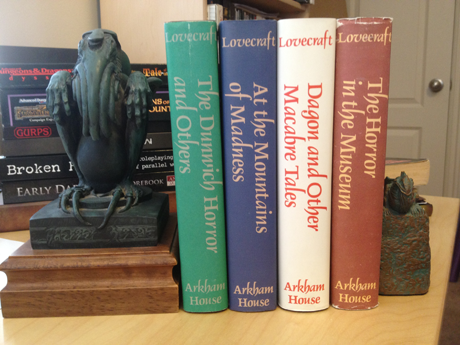

With all of that in mind, I recommend this Arkham House edition of The Dunwich Horror and Others (paid link). It’s the one I own, and if you like it there are three more Arkham House editions which together comprise all of Lovecraft’s fiction: At the Mountains of Madness (paid link) — which, disappointingly, I couldn’t locate on Amazon; this link is to a different edition — Dagon and Other Macabre Tales (paid link), and The Horror in the Museum (paid link). Finding them used at reasonable prices can sometimes be challenging, but it’s worth it.

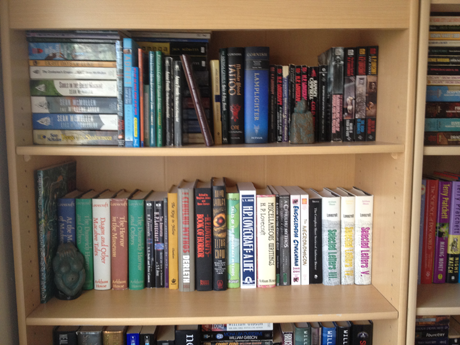

Those four books are the core of my Lovecraft library:

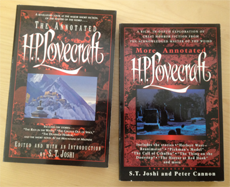

I also recommend S.T. Joshi’s annotated editions, which feature notes, photos, and other scholarship that’s anything but dry and boring: The Annotated H.P. Lovecraft (paid link) and More Annotated H.P. Lovecraft (paid link). I especially like the photos of locations that featured prominently in Lovecraft’s life and stories.

And, of course, as with most Appendix N books I’ve encountered so far the final recommendation is just read it. It doesn’t really matter which Lovecraft collection you start with — just start somewhere. If you love his tales as much as I do, you’ll quickly find yourself with plenty more to read.

Martin, please post the ISBN for the green cover edition of Dunwich Horror and Others? That edition has a sentimental connection for me, as it was the first lovecraft book I read as a teen.

More on topic, great post – I agree, I was at first mystified with Gygax’s interest in Lovecraft, as few early D&D modules seemed all that cosmic. But I think the tomes, and rituals, and some of the atmospheric elements definitely bled through into the DMG.

Great post.

Sure thing! It’s 0-87054-037-8, copyright 1963. My copies aren’t actually from 1963, as they’re both corrected seventh printings; I don’t know what year mine came out, but the ISBN and 1963 should be good for confirmation.

I have 3 of the 4 Arkham House collection from your photo. I am missing “The Horror In the Museum.” What is it’s ISBN? I would love to track it down so i can have a complete matched set.

It’s 0-87054-040-8, copyright and published in 1989, the corrected fourth printing. Happy hunting!

Thanks!

Oh man. Where can I get that awesome booked ND?

I’m not sure what you mean. But if it’s bookend, the left is a Bowen Design Cthulhu statue that’s long out of production, and the right is a bronze statuette sculpted by Rick Sardinha; I don’t know if he still makes them.